2024, the 650th anniversary of the death of Francesco Petrarca, marks the century of existence of the name of the bookshop, the Libreria antiquaria “Umberto Saba”..

As a young man reading a Petrarca commented on by Giacomo Leopardi, Saba rediscovered “the golden thread of the Italian tradition”. He attributed the title Canzoniere to the collections of poetry that made up his autobiography in verse, the same title adopted for the collection of the historic humanist’s Fragmenta.

In Storia e Cronistoria del Canzoniere he confessed: “Saba was, by temperament, a classicist, matured in a romantic environment”. (3). From the bookshop in via San Nicolò he obtained the Canzoniere by Francesco Petrarca, which Umberto Saba had in his possession (Padova, Minerva 1837). (9)

In Saba’s compositions critics recognise the search for the polished word as was used by Petrarch and Tasso, by Metastasio, Foscolo, Leopardi, and Parini. (2; 2bis) The poet from Trieste maintained the sequence of the collections of poems in a dimension outside of time, but observing a unity of place. Trieste is almost always the setting for his pieces. With Petrarch he shares the sense of an intimate solitude that cannot be resolved, due to his diversity from others.

“Only sometimes do I descend among the haughty / people of the world, there those worries of theirs / I feel, not severe silent cares, / but cruel struggles, and shame and damage” (Così passa i miei giorni). (3bis) Melancholy is a state of mind shared with Petrarch. The forty-year-old Saba in Storia e Cronistoria del Canzoniere, reveals: ““The melancholic” was, in Saba’s thought, Petrarch”” (5).

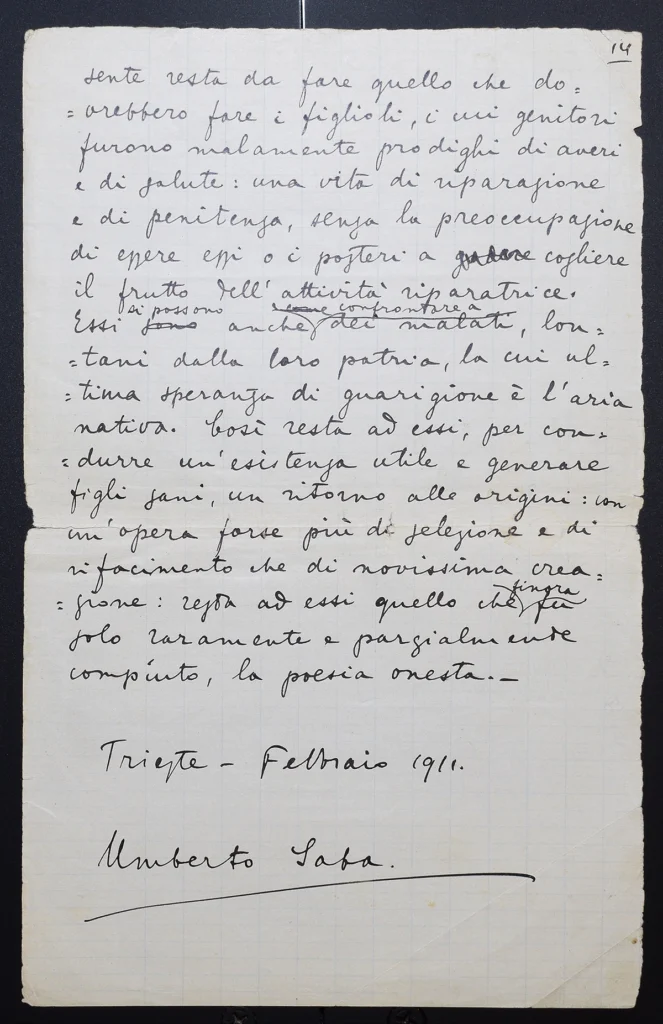

Umberto Saba invia l’8 febbraio 1911 il saggio alla rivista fiorentina «La Voce», che però non lo pubblica. Saba vi rivendica la testimonianza di ricerca di un valore etico della poesia.

Carta a quadretti, manoscritto a inchiostro di china cc. 14; misure 23 x 14,5 cm;

Provenienza : Università di Pavia, Centro per gli studi sulla tradizione manoscritta di autori moderni e contemporanei

SAB 02 29 c.14

Umberto describes the landscape as a serene counterpart to his own tormented “interiority”, replicating the landscape of humanistic poetry: “I love the seashore and the solitary countryside; …and a stream that responds to it among the stones or flowers” (Il Melanconico v. 4-5, 9) (4).

Even the sense of estrangement from others – “Only the vulgar offend me, he who drew me away / from my good…” (Il Melanconico v. 12-13) – takes up a recurring motif in Petrarchan poetry: “I find no other shield that can protect me from the manifest awareness of the people” (Francesco Petrarca, Solo et pensoso, RVF 35). In the Versi Militari: Durante una Marcia he expresses the burden of living and the awareness of his own diversity from other men: “And I, if at times I suffer from such a harsh life / that all my senses are offended; / believe, it is not the heaviness of the burdens, / it is the uselessness of the effort” (8).

This consonance with Petrarca is disavowed in the prose of his maturity. After psychoanalysis, which he undergoes with the psychiatrist Edoardo Weiss, Saba states in Scorciatoie: “Laura was the woman you cannot have. And the whole fascinating, slightly monotonous, story of the Canzoniere, of twenty and more years of courtship, to not arrive, to want to arrive at nothing, is here” (1945) (7; 7bis). To the critic Goffredo Bellonci who wondered if Laura ever really existed and concluded that Laura is a metaphor for Poetry, Umberto replied ironically that Laura was for the humanist a metaphor for the mother, but that for poets the mother is, precisely, Poetry itself (7).