Director of the Museums and Libraries Service

Laura Carlini Fanfogna

By Alessandra Sirugo

Collaboration

Maria Carolina Tamberlich

Administrative Coordination

Gloria Deotto

Administrative Collaboration

Pierpaolo Messina

Elisa Seminerio

Graphics

Lorella Klun

Photos

Franco Levi

Panels produced by

UtilGraph Snc

Translations

Quickline s.a.s. – Trieste

Frames produced by

Asso di Quadri di Dario Sfreddo

What did Dante and Petrarch read?

On the 7th centenary of Dante’s death (1265-1321), the Museo Petrarchesco Piccolomineo turns the spotlight on Dante’s influence on the poetry of Francesco Petrarca.

The parallel between the two poets remains central to the history of Italian poetry even today. They are separated by two generations.

Francesco (1304-1374) was born in Arezzo because his father Petracco, like Alighieri, had been banished from the Florentine Republic: a common destiny of exile in which Dante experienced hardship, poverty and dependence on the lords who hosted him.

Petracco, on the other hand, was a notary and managed to support his growing family by moving to Avignon. The city in Provence became a political and diplomatic crossroads from 1309, when the papal curia moved there. Francesco attended the School of Law in Bologna. When he arrived there in 1320 to spend a period of five years, Dante had been living in Ravenna for some time and his star was already bright.

What did they read?

The works of both reveal that they had read and assimilated the biblical texts.

Dante was familiar with Virgil’s works, having spent a long part of his exile in Verona, home of the Biblioteca Capitolare, one of the oldest libraries in Europe. He could count on a literary heritage he had read and memorised, consisting of a dozen classical and Christian writers: Virgil, the Ovid of the Metamorphoses, Statius, Lucan, Horace’s Ars poetica, Cicero’s De amicitia, and a selection of Provençal and Italian poets. If we accept the attribution of the Fiore to Dante, he had also read and assimilated the Roman de la Rose.

And what about Petrarch?

From a flyleaf of the Paris codex (lat. 2201) from his library, we discover the classification of his favourite readings: Virgil, Lucan, Statius, Horace, Ovid and Juvenal. He admired Horace’s Odes and in this he went against the ranking of that writer’s works most appreciated in the Middle Ages. Among modern writers, Petrarch read the troubadour Arnaut Daniel, Guittone d’Arezzo and his followers, Monte Andrea and Panuccio del Bagno, Cecco d’Ascoli, the Stilnovo poet Dino Frescobaldi and Boccaccio’s rhymes. But from his youth, Dante’s rime petrose and the Divine Comedy were central to his education.

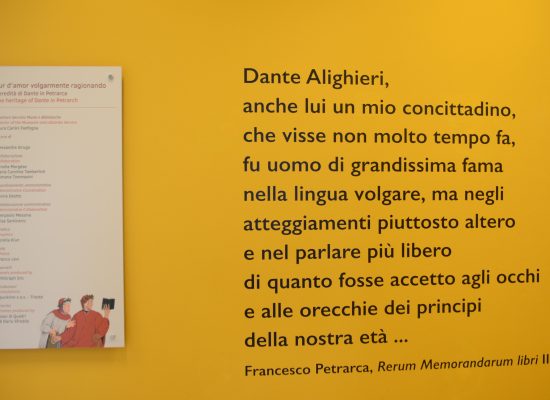

Was Dante too frank?

In the Rerum familiarum liber, an unfinished work, Petrarch narrates episodes from history on the model of the Memorable Deeds and Sayings of the Roman Valerius Maximus (1st century BC – 1st century AD). The work is a catalogue of moral examples centred on the cardinal virtues of figures from the classical age, to which some modern ones are added, as Francesco does in the Triumph of Fame.

Among the personalities of the Middle Ages, he describes Robert of Anjou, Pope Clement VI and Dante. He leaves us a portrait of Dante as a great author in the vernacular, not always appreciated by princes for his proud and outspoken character. In fact, he tells us that, during his exile, the poet was well received by Cangrande della Scala in Verona, but was soon cast aside. The court was frequented by buffoons and layabouts, one of whom was as amusing as he was intrusive. Cangrande suspected that Dante could not stand the exuberant fellow-guest and put him in an embarrassing situation. He called the insolent guest, praised him and remarked, “I am amazed that this man, despite being crazy, is liked by everyone, unlike you, who are reputed to be wise.” The poet replied that people sympathise with those who are like them: he ascribed to Cangrande the lowliness of his guest, an unforgivable provocation, and in fact, Dante left Verona in 1318.

Francesco then adds the episode in which Dante was sitting at the table of a noble family and the gentleman, already tipsy and sweaty from overeating, was talking nonsense, while Dante was silent. The host then asked for his approval, “Do you not know that he who speaks the truth does not get tired?” to which the poet replied sharply, “And I was wondering what was making you sweat so much.”

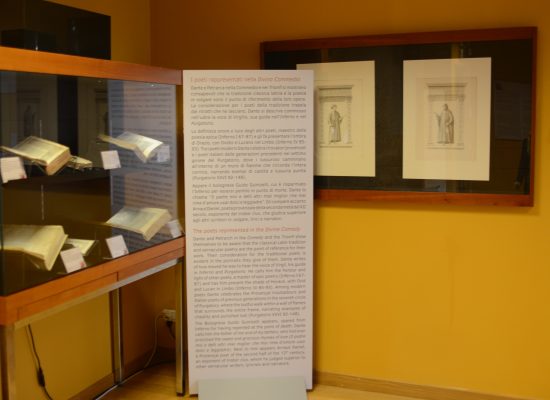

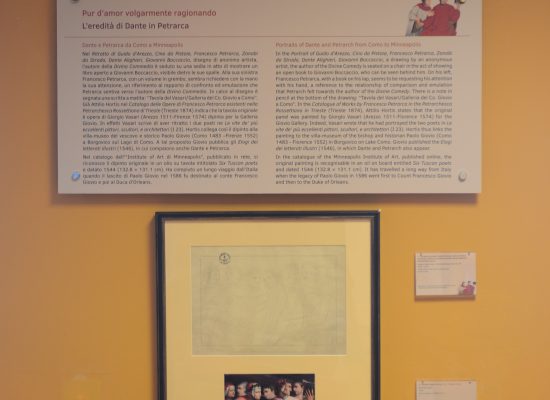

Portraits of Dante and Petrarch from Como to Minneapolis

In the Portrait of Guido d’Arezzo, Cino da Pistoia, Francesco Petrarca, Zanobi da Strada, Dante Alighieri, Giovanni Boccaccio, a drawing by an anonymous artist, the author of the Divine Comedy is seated on a chair in the act of showing an open book to Giovanni Boccaccio, who can be seen behind him. On his left, Francesco Petrarca, with a book on his lap, seems to be requesting his attention with his hand, a reference to the relationship of comparison and emulation that Petrarch felt towards the author of the Divine Comedy. There is a note in pencil at the bottom of the drawing: “Tavola del Vasari/ Galleria del Co. Giovio a Como”. In the Catalogue of Works by Francesco Petrarca in the Petrarchesca Rossettiana in Trieste (Trieste 1874), Attilio Hortis states that the original panel was painted by Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo 1511-Florence 1574) for the Giovio Gallery. Indeed, Vasari wrote that he had portrayed the two poets in Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori (I 23). Hortis thus links the painting to the villa-museum of the bishop and historian Paolo Giovio (Como 1483 – Florence 1552) in Borgovico on Lake Como. Giovio published the Elogi dei letterati illustri (1546), in which Dante and Petrarch also appear.

In the catalogue of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, published online, the original painting is recognisable in an oil on board entitled Six Tuscan poets and dated 1544 (132.8 × 131.1 cm).

It has travelled a long way from Italy when the legacy of Paolo Giovio in 1586 went first to Count Francesco Giovio and then to the Duke of Orleans.

The poets represented in the Divine Comedy.

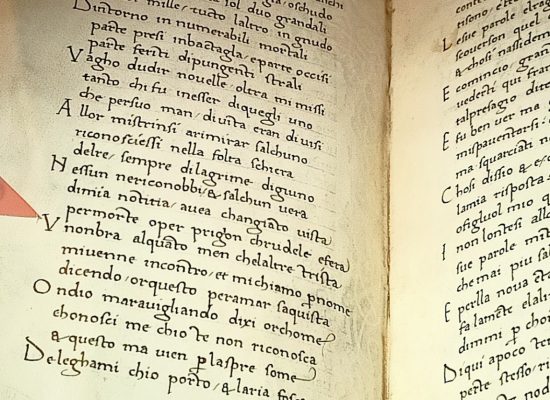

Dante and Petrarch in the Comedy and the Trionfi show themselves to be aware that the classical Latin tradition and vernacular poetry are the point of reference for their work. Their consideration for the traditional poets is evident in the portraits they give of them. Dante writes of how moved he was to hear the voice of Virgil, his guide in Inferno and Purgatorio. He calls him the honour and light of other poets, a master of epic poetry (Inferno I 67-87) and has him present the shade of Horace, with Ovid and Lucan in Limbo (Inferno IV 85-93). Among modern poets Dante celebrates the Provençal troubadours and Italian poets of previous generations in the seventh circle of Purgatory, where the lustful walk within a wall of flames that surrounds the entire frame, narrating examples of chastity and punished lust (Purgatorio XXVI 92-148). The Bolognese Guido Guinizelli appears, spared from Inferno for having repented at the point of death. Dante calls him “the father of me and of my betters, who had ever practised the sweet and gracious rhymes of love”. Next to him appears Arnaut Daniel, a Provençal poet of the second half of the 12th century, an exponent of trobar clus, whom he judged superior to other vernacular writers, lyricists and narrators.

The chests with the Triumphs

The Triumphs of Love, Chastity and Death

Petrarch composed the poem in the vernacular using the composition format of a vision, like the Divine Comedy. He is the narrator and protagonist of the dream in Valchiusa in 1351, in which Love appears to him on a chariot drawn by four horses. He is addressed by a shade, perhaps Sennuccio del Bene, who offers to accompany him and describes Love’s victims: the heroes of Hellenic tragedy, including Hercules, who disguised himself as a woman to approach Omphale, and Leander, who drowned trying to reach his beloved Hero. He then recognises certain characters consecrated by Dante to literary existence. Virgil is remembered for the pastoral loves sung in the Bucolics and the Georgics. He is accompanied by Ovid, Catullus, Propertius and Tibullus (T. A. IV 19-24). Among the figures on the two chests is Virgil, hanging from a basket by his woman Fibille.

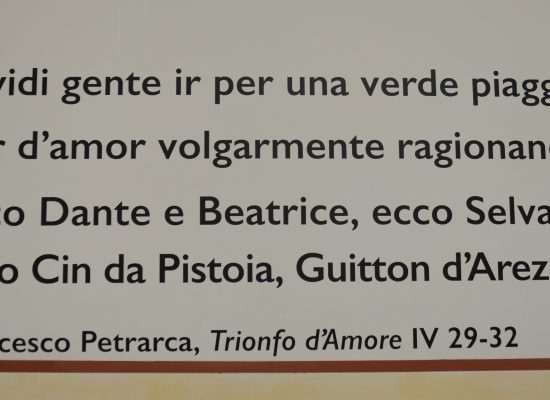

Petrarch calls Dante to open with Beatrice the group that proceeds through a green meadow, discoursing of love in the common tongue. Next to them appear Cino da Pistoia and Selvaggia, Guittone d’Arezzo, Guido Guinizelli with Guido Cavalcanti, and the Provençal poets (T. A. IV 28-60). The poet uses the verb “to discourse”, employed by Dante (Purg. XXVII 53) and found in Dante’s sonnet Guido I’vorrei che tu e Lapo ed io. Dante and Cino are the only exponents of Italian poetry that Petrarch depicts next to their beloveds, a sign that the Dolce stil novo and the theme of the Madonna as the inspiration of poetry were already well established.

In the lower part of the two panels appears Aristotle, on all fours being ridden by Phyllis. Next to him is Samson, whose hair was cut off by Delilah. The lower front of the chest bears the coat of arms of the Ridolfi di Piazza and Cavalcanti families, one of whose descendants, Lorenzo, married Margherita Cavalcanti in 1467.

In the Triumph of Chastity, Laura appears to Petrarch, fresh from her duel with Love, portrayed with a book and a laurel branch. Her chariot is pulled by a pair of unicorns and preceded by sixteen female virtues. She is followed by ten women who bore witness to modesty in their lives. The procession of Love and Chastity reaches the Temple of Pudicitia in Rome, where the poet sees the black banner foretelling Laura’s death: it is the first hour of 6 April 1348.

Death plucks a hair from Laura’s head and a vast plain strewn with corpses appears over the whole surrounding space.

The Triumphs of Fame, Time and Eternity

From the green plain Petrarch then glimpses Fame, which preserves the memory of exemplary personalities. The chariot is drawn by a pair of elephants. In the chest painted by Domenico di Zanobi, Fame appears wrapped in a golden almond-shaped nimbus, as in Giovanni Boccaccio’s L’amorosa visione (1342; chap. VI).

Fame carries a sword in her right hand and scales in her left, symbols of Justice.

On the other hand, in the panel by the workshop of Marco del Buono and Apollonio di Giovanni, Fame is wrapped in a dark cloak and holds a sword in her right hand, while in her left hand she holds a golden sphere on which there is a statuette of the god Love.

In the Third Triumph of Fame, military leaders and men of thought appear, led by scientists and classical authors. Among them, Virgil marches next to Homer (T. F. III 10-17):

… e quello ardente

vecchio a cui fur le Muse tanto amiche ch’Argo e Micena e Troia se ne sente;

questo cantò gli errori e le fatiche

del figliuol di Laerte e d’una diva, primo pintor delle memorie antiche. A man a man con lui cantando giva il Mantovan che di par seco giostra,

The Triumph of Time features the Sun, which accelerates its course through the sky, dragging human beings and their memories towards the void. The artists on both sides of the chest depict Saturn in the centre of the Triumph, with his chariot drawn by a pair of deer. Petrarch sees how the events of man fade away (T. Tem. 112-117):

Passan vostre grandezze e vostre pompe, passan le signorie, passano i regni;

ogni cosa mortal Tempo interrompe,

e ritolta a’men buon, non dà a’ più degni;

e non pur quel di fuori il Tempo solve, ma le vostre eloquenzie e’ vostri ingegni.

Lastly, the author witnesses the Triumph of Eternity. Among the beautiful and rare souls, the most blessed is destined to be Laura (T. Et. 82-87)

O felici quelle anime che’n via sono o seranno di venire al fine

di ch’io ragiono, quandunque e’si sia!

E tra l’altre leggiadre e pellegrine, beatissima lei che Morte occise assai di qua del natural confine!

The court of heavenly souls tells the poet that on the day of judgement God will recognise and reward merits and demerits, and the souls will head towards the place for which they are destined. In a golden frame, Christ triumphs on the top of the universe.

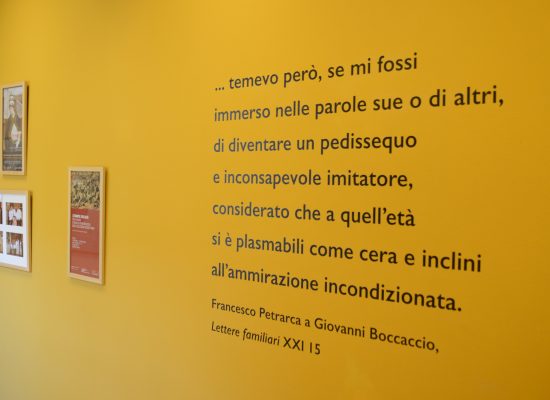

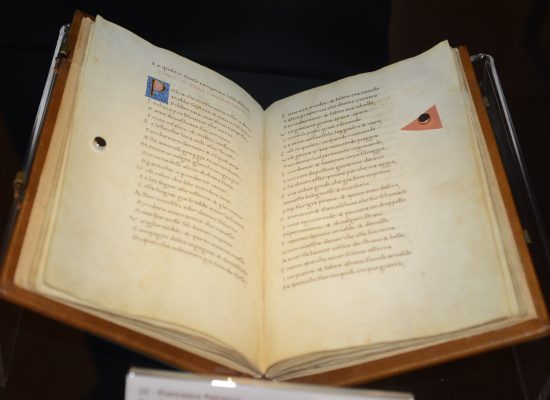

The friendly letter to Giovanni Boccaccio who gave him the Divine Comedy

Petrarch avoids comparison with Dante. In the spring of 1351 Boccaccio visited him in Padua and reproached him for not having the Comedy. On his return to Florence, Giovanni sent him a copy, now preserved in the Vatican Library, the Vatican Codex 3199, accompanying it with his own poem Italie iam certus honos.

In 1359, after visiting Petrarch in Milan, Giovanni once again stressed the value of the Divine Comedy.

His friend responded to the prompt with the Lettera Familiare XXI 15, in which he underlined Dante’s inimitable character, but claimed to have sought another way to express himself.

He complained that the author of the Comedy was appreciated by the common people, who did not understand its depth. He recalled that he was just a child when he met Dante, who devoted himself entirely to the project of the Comedy, even neglecting his own family for the sake of fame.

Dante was exceptional in his kind of poetry, but the humanist proudly claimed to be a new kind of intellectual. He also showed his appreciation of Dante in the Comedy and the Rime in the vernacular, but believed that in the Latin works the poet was not always up to his own standards. He replied that he did not possess the Comedy for fear of being influenced by the author and becoming an imitator. If there are words or expressions in his poetry that refer to Dante, this is by chance: he tried to erase the traces of his dependence on Dante’s vernacular work, but implicitly admitted that his Canzoniere was influenced by it.

The friends of Dante and the young Petrarch

Dante and Petrarch had some friends who were exponents of the Dolce Stil Novo.

The first is remembered by Petrarch’s friends as Sennuccio del Bene (1270 ca. – 1349), who from 1313 had his property confiscated and was exiled from Florence. According to a certain tradition, he even corresponded with Dante. The author of the Comedy is credited with the sonnet Sennuccio, la tua poca personuzza, a playful response to the song Amor tu sai ch’io son col capo cano, in which del Bene expresses his unease at having fallen in love at an advanced age. The song reveals that he was familiar with the Divine Comedy, for he writes “tu se quel che a nullo amato amar perdona”, a verse in which Dante makes Francesca da Rimini, lover of her brother-in-law Paolo Malatesta, express the strength of her passion (Inferno V 103). But there are even people who speculate that Dante may have noticed the famous verse in Sennuccio’s song and reproposed it in the Comedy.

In Avignon he met Petrarch, with whom he carried on a dialogue until the end of the 1340s. The letter on Petrarch’s coronation in the Campidoglio in 1341, printed several times as his since 1549, turned out to be a 16th-century forgery. According to some commentators, Sennuccio is the friend who guides Francis in the Triumphs: “vero amico ti sono; and teco nacqui in terra Tosca“. The author gives him a prominent place in the procession of poets in the Triumph of Love (IV 33 ff.) together with Guido Guinizzelli and Guido Cavalcanti.

When he died, around 1349, in the Canzoniere, Petrarch dedicated the composition Sennuccio mio, benché doglioso et solo to his lifelong friend, including him in his poetic pantheon together with Guittone d’Arezzo, Cino da Pistoia, Dante and Franceschino degli Albizzi:

ma ben ti prego che’n la terza spera / Guitton saluti, et messer Cino, et Dante, / Franceschin nostro, et tutta quella schiera.

Dante scholars in Trieste and along the north-eastern Adriatic

Dante’s fortunes on the eastern Adriatic began with the humanists of Petrarch’s generation: Nicolò d’Alessio from Koper (1320-1393), chancellor in Isola d’Istria (now Izola in Slovenia), Pietro Campenni from Tropea, who transcribed an annotated codex of the Comedy in Izola, Giovanni Conversino from Ravenna, public teacher in Muggia in 1407. The following century saw the publication of the Regole grammaticali della volgar lingua (Grammatical rules of the common tongue) by Gianfrancesco Fortunio, vice-governor of Trieste from 1497, focusing on textual criticism. In the 17th century in Piran, Count Marco Petronio Caldana composed the Clodias, the 9th canto of which tells the story of Clotilde’s journey through Paradise. In the Age of Enlightenment, Gian Rinaldo Carli, in book IV of Le antichità italiche (Italian antiquities), argues in favour of the vernacular evidenced by the writings of educated people from different regions, taking up the theories expressed by Dante in DeVulgari eloquentia.

Trieste can boast an intense tradition of studies in the nineteenth century by collectors, such as Domenico Rossetti and Marco Besso, writers – Francesco dall’Ongaro and Filippo Zamboni -, and philologists, led by Attilio Hortis and Salomone Morpurgo.

Domenico Rossetti, who donated incunabula and sixteenth-century Dante books to the Biblioteca Civica, published in Milan “Perché Divina Commedia si appelli il Poema di Dante, dissertazione di un italiano” (Why the Divine Comedy is called Dante’s Poem, dissertation by an Italian) (1819). Francesco dall’Ongaro settled in Trieste in 1836 and became director of the magazine “La Favilla”. His Lectures on Dante were inspired by his Risorgimento convictions, as was the public Lectura Dantis announced in the journal on 19 July 1846. Filippo Zamboni, a lecturer in the capital of the Empire, wrote Gli Ezzelini, Dante e gli schiavi (The Ezzelini, Dante and the Slaves) (1880) and Il fonografo e le stelle e la visione del Paradiso di Dante (The phonograph and the stars and Dante’s vision of Paradise). Sogni d’un poeta triestino (Dreams of a Trieste poet) (1901), expressing a taste for contaminations of literature and applied science. Marco Besso, founder of the Assicurazioni Generali Group, was the author of two essays on Dante. A friend of Nicolò Tommaseo, he created an impressive library and set up the Foundation of the same name in Rome dedicated to the great poet. Attilio Hortis left us the essay Dante e il Petrarca (Dante and Petrarch). Nuovi studii (New studies) (Rivista europea, 1875) and the review of Dante, secondo la tradizione e i Novellatori (Dante, according to tradition and the novella writers) by Giovanni Papanti (1873). Salomone Morpurgo, director of the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, published I codici riccardiani della Divina commedia (The Riccardi codices of the Divine Comedy) (1893), the first of the catalogues of Italian manuscripts that he edited. He is remembered for his original method of investigating the manuscript tradition and for the Supplement to Zambrini’s catalogue, Le opere volgari a stampa dei secoli XIII e XIV (Printed vernacular works of the 13th and 14th centuries) (1929), fundamental for the study of Dante’s texts and of the early commentators.

The most significant studies in the last century were the work of Bruno Maier, author of numerous Lecturae on Dante and editor since 1962 of reprints of U. Cosmo’s Opere dantesche. Among Slovene-speaking scholars, we should mention Alojz Rebula, a Catholic intellectual, who in his collection of essays Da Nicea a Trieste (From Nicaea to Trieste) counts Dante among his reference authors.